Tiger

Panthera tigris

IUCN Red List: Endangered

| Weight: | 75-325 kg |

| Body length: | 150-230 cm |

| Tail length: | 90-110 cm |

| Longevity: | 12-15 years |

| Litter size: | 1-5 cubs |

Description

The tiger (Panthera tigris) evolved, along with other modern felids in the Panthera lineage, from an ancestral cat species around 10.8 million years ago. Several million years later, the tiger branched off along with the other "great roaring cats" of the modern Panthera genus. The oldest known tiger fossils, approximately 2 million years old, were found in China and on Java, Indonesia.

The tiger once ranged throughout southern and eastern Asia. Approximately 73,000 years ago, the Toba volcanic eruption on Sumatra may have resulted in a major range reduction, population bottleneck, and resultant decreased genetic variation in the survivors. The most recent common ancestor for tiger matrilineal mitochondrial DNA is estimated to have originated 72,000-108,000 years ago.

The modern tiger was considered to consist of six extant and three extinct subspecies. The six living tiger subspecies are organised based on distinctive molecular markers:

- Amur tiger P. t. altaica inhabiting the Russian Far East and north-eastern China

- South China tiger P. t. amoyensis, likely extinct in the wild and currently known only in captivity

- Northern Indochinese tiger P. t. corbetti occurring in Indochina north of the Malayan peninsula

- Malayan tiger P. t. jacksoni living on the Malayan peninsula

- Sumatran tiger P. t. sumatrae found on Sumatra

- Bengal tiger P. t. tigris inhabiting the Indian sub-continent.

The three recognised extinct tiger subspecies based on morphological differences are:

- Bali tiger P. t. balica, once living on the island of Bali

- Javan tiger P.t. sondaica once living on the island of Java

- Caspian tiger P.t. virgata, once found in western Asia, including: Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Iraq, Iran, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

However, based on recent studies, only two tiger subspecies are proposed:

- Panthera tigris tigris (including virgata, altaica, amoyensis corbetti and jacksoni) in mainland Asia including India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan, Sikkim, China, Russia, Indochina and the Malay Peninsual and

- Panthera tigris sondaica (including balica and sumatrae) on Sumatra and formerly Java and Bali

These inconsistencies in the number of proposed tiger subspecies are thought to partly be a result of the lack of genetic samples across the tiger range. Given the varied interpretations of data, the taxonomy of this species is currently under review by the IUCN SSC Cat Specialist Group.

Subspecies | Weight (kg) | Total length (m) | Skull length (mm) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

Altaica | 180-306 | 100-167 | 2.7-3.3 | 2.4-2.75 | 241-383 | 279-318 |

Amoyensis | 130-175 | 100-115 | 2.3-2.65 | 2.2-2.4 | 318-343 | 273-301 |

Balica | 90-100 | 65-80 | 2.2-2.3 | 1.9-2.1 | 295-298 | 263-269 |

Corbetti | 150-195 | 100-130 | 2.55-2.85 | 2.3-2.55 | 319-365 | 279-302 |

Sondaica | 100-141 | 75-115 | 2.48 | 306-349 | 270-292 | |

Sumatrae | 100-140 | 75-110 | 2.2-2.55 | 2.15-2.3 | 295-335 | 263-294 |

Tigris | 180-258 | 100-160 | 2.7-3.1 | 2.4-2.65 | 329-378 | 275-311 |

Virgata | 170-240 | 85-135 | 2.7-2.95 | 2.4-2.6 | 316-369 | 268-305 |

The tiger is the largest living cat species, although there is considerable variation among subspecies and large lions can be larger than smaller tigers. The tiger is the only cat species with stripes. It has a reddish-orange to yellow-ochre coat with black stripes and a white belly. The stripe patterns are unique to individual tigers. The stripes vary in number, as well as width and propensity to split and run to spots. The dark lines above the eyes tend to be symmetrical, but the marks on the sides of the face can be different. Males have a prominent ruff which is especially marked in the Sumatran tiger. In India, tigers with a white coat, ashy grey or brown stripes, and blue eyes, have been described from the forests of Assam, Orissa, Madhya Pradesh and Bihar. The last record of a white tiger shot in Bihar is from 1958. Since then, there were no recent reports of white tigers from any part of India.

The tiger evolved to effectively hunt and kill large ungulates. It has a relatively large skull with extraordinary canines and a powerful overall build.

Language/Country | Name |

|---|---|

English | Tiger |

French | Tigre |

Spanish; Castillian | Tigre |

Achinese | Rimueng |

Bengali | Baagh |

Chinese | Laohu |

Dzongkha | Taag |

German | Tiger |

Gujarati | Vagha |

Hindi | Baagh |

Indonesian | Harimau |

Javanese | Macan |

Kannada | Huli |

Lao | Sue yai, sua khong, sua lay |

Malayalam | Katuva |

Russian | Tigr |

Sundanese | Maung |

Tamil | Suex krong, seua |

Thai | seua |

Vietnamese | Con ho |

Farsi | Babr |

Tibetan | Rag |

Udege, Amur river region (Russian) | Amba darla |

- Bengal tiger, India.

- Amur tiger.

- Amur tiger.

- White tiger in Madrid Zoo.

Status and Distribution

The tiger is listed as Endangered by the IUCN Red List. In 2009, the in situ tiger population was estimated to be around 3,200 individuals with likely fewer than 2,500 mature animals. This represents a significant decline from an estimated 100,000 living at the beginning of the 20th century. Many tiger populations are very small and isolated. The tiger populations from 42 protected sites with evidence of breeding were estimated to number only 2,154 individuals in 2010. Population estimates of tigers outside protected areas are less known. In 2021, the global population size of tigers is estimated at 3,726–5,578 individuals excluding cubs (with an estimated average of 3,140 mature individuals) based largely on capture-recapture and occupancy methodologies. Tigers are now restricted to ten countries, namely those of Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Russia and Thailand. Over the past three generations, tigers have undergone a range contraction of >50% resulting in a suspected population reduction of >50%.

Country/Region | Estimated population size | Trend |

|---|---|---|

Bangladesh | 114 (89–146) | Unknown |

Bhutan (Royal Manas NP and Jigme Singye NP) | 103 (89–124) | Stable |

China | ~20 | Increasing |

India | 2,967 (2,602–3,346) | Unknown |

Indonesia | 393 (173–883) | Declining |

Lao PDR | 0 | Extirpated |

Malaysia | <100 | Declining |

Nepal | 235 (220–274) | Stable or decreasing |

Russia | 386 (265–486) | Stable |

Thailand | 145–177 | Increasing |

Viet Nam | 0 | Extirpated |

Total | 4,485 (3,726–5,578) | |

Total mature individuals | 3,140 (2,608–3,905) |

Tiger density varies. In India's Kaziranga and Corbett National Parks with abundant prey, densities of 15-19 animals/100 km² and in the Sikhote Alin Mountains in Russia with low prey availability, densities of 0.13-0.45/100 km² have been estimated. Generally, tiger densities are higher in alluvial flood plains and tropical deciduous forests than tropical moist, evergreen forests of South and Southeast Asia and temperate habitats of far East Asia.

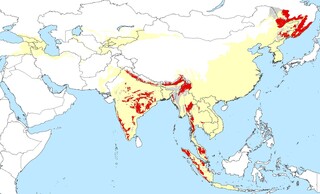

The geographic distribution of the tiger once extended across Asia from eastern Turkey and the southern parts of the Caspian Sea to the Sea of Okhotska (eastern coast of Russia). Today, an estimated 7% or less of its original historical range remains. Breeding subpopulations are confirmed in Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Russia and Thailand. The tiger has disappeared from modern-day Afghanistan, Georgia, the islands of Bali and Java in the Republic of Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Singapore, South Korea, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. In the last 100 years, tigers have disappeared from Singapore (1930s), Bali (1940s), Java and Hong Kong (1960s), central Asia (1970s), most of the mainland temperate (1980s) and tropical (1990s) China, and more recently from the Southeast Asian countries of Viet Nam, Lao PDR and Cambodia (2000s). Between 2001 and 2020, tiger range has decreased by 7% from 1,049,430 km2 to 978,293 km2. In the latest assessment, 71 Tiger Conservation Landscapes were identified. Of these TCLs, however, only 21% is legally protected and only 9% is protected in IUCN Categories I and II (i.e. strictly protected). Additionally, management was found to be poor due to constraints on regulation, budget and enforcement, and hunting was found to be a main threat. In 2010, 42 source sites were identified across the tiger range by Walston et al. Source sites were identified as sites with confirmed tiger presence, evidence of breeding, population estimates of over 25 breeding females, legal protection, and sites that were embedded in larger landscapes that would be able to host over 50 breeding females. Since the publication of Watson et al’s study, however, tigers have been extirpated from the only source site in Lao PDR, and several source sites were estimated to host less tigers than previously thought. On the other hand, some additional source sites that meet the criteria have also been documented, especially in South Asia. Globally, it is likely that over 60% of tiger populations can be found in protected areas.

Habitat

The tiger is found in a variety of habitats such as the tropical, subtropical and temperate evergreen and deciduous forests in South and Southeast Asia, and the coniferous, scrub oak, and birch woodlands of the Russian Far East. They are habitat generalists and also thrive in the mangrove swamps of the Sundarbans, the dry thorn forests of northwestern India and the tall grass jungles at the foot of the Himalayas. The tiger can be found from the lowland swamp forests of Sumatra to the dry high altitude areas of Bhutan, where it has been recorded up to 4,500 m above sea level. The main habitat requirements of a tiger are dense vegetation cover, access to water and sufficient large ungulate prey.

- Bengal tiger in Kanha, India.

- Habitat of the Bengal tiger, Pench, India.

Ecology and Behaviour

The tiger is a solitary animal. Females require and maintain individual territories. Males disperse sometimes over long distances and their territories often overlap with 1–3 females. The size of individual home ranges can be large and females must aggressively defend the resources within their home range while males have to search extensively and compete for available mates. The sizes of home ranges vary in accordance with prey densities. While females need ranges suitable for raising cubs, males seek access to females and have larger ranges. In areas rich in prey throughout the year (e.g., Nepal’s Chitwan National Park), studies have found female home ranges averaging 10-39 km² in size and male home ranges around 30-105 km². In the Russian Far East where prey is unevenly distributed and moves seasonally, home ranges can reach 100–400 km² for females and averaging 1,379 km² for males. In the Sundarbans of Bangladesh female home range size have been found ranging from 12.3 to 14.2 km². Similarly, tiger densities vary in accordance to prey availability with values as high as 15–19 tigers per 100 km² being reported in areas with high prey availability (India's Kaziranga and Corbett National Parks) and as low as 0.13–0.45 tigers per 100 km² reported for areas with low prey availability (Russia’s Sikhote Alin Mountains).

The tiger is an obligate terrestrial carnivore. It ambushes its prey but also actively searches for prey species. It often drags its kill to nearby cover to feed on. It hides the parts which have not yet been consumed and generally returns to feed on it.

The reproduction season depends on the region. Studies have found that reproduction can take place year-round: from December to February in Manchurei, from November to April in India, and birth peak from May to July in Nepal. Estrus lasts for seven days and the estrus cycle for 15 to 20 days in Rajasthan (India). Others reported estrus cycles of 46 to 52 days and 34 to 61 days. If a litter is lost, estrus occurs within a few weeks (mean 17 days, range 10-39). Gestation lasts for approximately 103 days. The interbirth interval is on average 20 to 24 month, but can last up to 36 months. However, if the litter is lost in the first two weeks, the interval can be 8 months. Age at independence is 18 to 28 months. In Chitwan, first-year cub mortality was around 34% of which 73% was whole litter loss due to causes including fire, floods and infanticide. Mortality in the second year of life was 17% of which only 29% was whole litter loss. Infanticide was overall the most common cause of cub death. Studies have suggested that populations decline when the mortality of breeding females exceeds 15%.

Data collected over nearly 20 years by the long-term tiger population monitoring project at Nepal’s Chitwan National Park found the average reproductive life span of tigers to be 6.1 years for females and 2.8 years for males. Age at first reproduction is at 3.4 years for females and at 4.8 years (3.4-6.8 years) for males. Age at last reproduction was recorded at 14 years. The mean number of offspring surviving to dispersal was estimated at 4.54 for females and the average number of offspring eventually incorporated into the breeding population was just 2.0. For males an average of 5.83 of their offspring survived to dispersal and 1.99 were incorporated into the breeding population.

- Bengal tiger in a river in Pench, India.

- Amur tigers.

- Bengal tigers in Kanah, India.

- Tiger claw marks on a tree, India.

Prey

The main prey species of the tiger are large ungulates such as chital (Axis axis), gaur (Bos gaurus), sambar (Cervus unicolor), wild pig (Sus scrofa) and muntjac (Muntiacus muntjak). The tiger also preys on red deer, roe deer, peafowl and musk deer. Generally, wild pig and deer of various species form a large part of their diet. The tiger sometimes kills livestock and small prey such as hares. The diet of the tiger is biogeographically diverse. In India, its diet consists of chital, sambar, nilgai, chinkara, wild pig and common langur make part of its diet. In Cambodia, the major prey species are barking deer, wild boar, sambar, gaur and banteng. Tigers need around 50-60 large prey animals per year. When large prey population, however, are depleted, tigers opportunistically prey on smaller prey such as birds, fish, rodents, insects, amphibians and mammals (e.g. porcupines or primates). They are capable of taking down prey much larger than themselves including large bovids such as water buffalo and rarely even animals such as the Asian elephant or rhino. Preferred prey, however, are in the same weight class as tigers themselves.

Main Threats

One of the main threats to the tiger today is illegal hunting and poaching. Tigers were once widely hunted for sport and trophy hunting. Legal and illegal hunting of tigers also occurred widely throughout the 19th and much of the 20th century to prevent conflict or in retaliation for conflict between tigers, people and property. Despite tigers being protected and international commercial trade being prohibited nowadays, tiger trade still occurs in non-government-controlled areas, such as northern Myanmar bordering China. They are killed to supply the illegal trade in tiger skin, bones, meat and other body parts, particularly for use in traditional East Asian medicines. Law and regulation enforcement can be complicated and the consumption of tiger body parts is deep-rooted in some cultural practices across countries in the tiger’s range. Tiger skins and other body parts can be sold for a lot of money, i.e. for USD 10,000–70,000. Certain body parts (e.g. skins, claws and canines) can be used as display items by elite society members. These practices, however, are thought to have reduced, although tiger skins still are worn and traded in western China and Tibet. Tiger bones, meat and organs, whiskers, urine and scats are all believed to possess healing properties in Traditional Chinese medicine. To meet rising demand for tiger bone, similar species such as lion, jaguar and other species such as leopards and clouded leopard have also been implicated in this trade. Additionally, there have been increasing reports of tiger farming and captures of wild tigers to stock breeding programmes. In China there are so called tiger farms in place with intensive breeding of captive animals and which produce illegally tiger bone wine.This illegal trade is contributing to the rapid disappearance of tigers from much of its current range.

Another major threat is habitat loss and degradation due to infrastructure development, human settlements, logging, conversion of land for agriculture or silviculture, and land clearance for plantations such as oil palm or rubber plantations. Such activities also increase human access to forest areas for poaching. The tiger has lost over 93% of its historical range. Asia is a densely populated, rapidly developing region bringing increasing pressures onto the large areas required for viable tiger subpopulations. Increasing human populations and settlements, agricultural expansion, and other economic development have led to the loss and fragmentation of tiger habitat.

Many tiger populations are isolated and a growing number are so small that genetic inbreeding is a serious concern. Tigers can become locally or functionally extinct in areas where habitat connectivity is severed or severely compromised.

The main prey species of the tiger are also under high pressure from hunting, habitat loss and degradation, and competition from people and domestic livestock. The type and density of prey influence many characteristics of tiger population biology, including reproduction and survival. Loss of adequate prey species can be an important predictor of tiger population health.

Direct and indirect conflict between tigers and humans and their property has historically been a major source of tiger mortality and remains an important threat today. Tigers may kill livestock and have attacked or killed people everywhere tigers and people coexist. This conflict often has led affected individuals and communities to retaliate by using lethal control to remove tigers using guns, poison, traps, or other methods. Some tigers are captured and moved or placed in captive breeding facilities by authorities following attacks on people or livestock. Tiger-human conflict contributed significantly to the eradication of tigers from western Asia, the island of Java, Singapore, and large swaths of China and the Russian Far East. The retaliatory killing of tigers in response to attacks on people and livestock is common and often assumed to be a significant cause of population decline. Tiger attacks can result in intolerance towards tigers and can present significant challenges when trying to build local support for tiger conservation.

Infectious diseases in tigers still are poorly understood. Several tiger deaths (e.g. in Sikhote-Alin Zapovednik in Russia), however, have been attributed to canine distemper virus infection. Additionally, disease can also impact tiger prey (e.g. African Swine fever in Russia and Indonesia) and further contribute to prey depletion.

All of these threats were likely responsible for the extinction of the Bali, Javan, and Caspian tigers. Habitat was converted and fragmented, critical ungulate prey were lost through disease and over-hunting by humans, and hunting of tigers for sport and official eradication programmes likely played a role in their historical decline. Illegal trade in tigers together with depletion of their prey base led to the recent disappearance of tigers from areas with otherwise suitable habitat.

Conservation Effort and Protection Status

The tiger is included in Appendix I of CITES. The tiger is protected over most of its range and commercial trade is long prohibited. Hunting is prohibited in Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Russia, Thailand and Vietnam. There is no information for North Korea available.

Various initiatives have been launched to conserve the species and many tiger conservation efforts have been undertaken at local, regional, national, and international scales. Among the most notable early conservation efforts, "Project Tiger" was launched in India in 1973 as a nationwide effort to counter the disappearance of tigers in that country. Project Tiger contributed to the establishment of dedicated tiger reserves throughout India. Over the past several decades many other countries have launched their own tiger conservation efforts, with varying success.

Recognising the crisis facing tigers and tiger habitat throughout Asia, political leaders of the 13 tiger range states and representatives of conservation NGOs and donor organizations signed the St. Petersburg Declaration (a Global Tiger Recovery Program) in 2010, with the goal to stabilize and eventually double the population of wild tigers by 2022 to at least 6,000 individuals. The following goals and actions are intended to help reach that goal:

- Preserve, manage, enhance and protect tiger habitats;

- Stop poaching, smuggling and illegal trade of tigers, their parts and derivatives;

- Cooperate in transboundary landscape management;

- Work together to combat illegal trade;

- Include indigenous and local communities in planning and implementation;

- Increase the effectiveness of tiger and habitat management; and

- Restore tigers to their former range.

Recognition among policy makers that economic development, conflict over land use, human-wildlife conflict, and domestic and international trade in wildlife are major threats to the survival of tigers will be necessary for long-term conservation to succeed.

There is widespread agreement that conservation of large and suitable habitats for tigers is needed, including the linking of core tiger populations. Landscape analyses have estimated that tiger reserves could support more than double current tiger numbers but that national and international commitment and cooperation for conservation will be crucial for success. “Source” populations and core protected tiger areas are unevenly distributed and may represent only 6% of current tiger range. Protecting and monitoring these remaining breeding populations, establishing and protecting corridors and transboundary conservation areas to support gene flow among disjunctive populations, are conservation priorities. Additionally, improvement of management effectiveness of existing protected areas too is critical for the recovery of tigers, this will also require the empowering and enabling of local communities living in and around tiger habitats.

Reduction in human-caused mortality of tigers and tiger prey is also crucial for long-term survival of tigers in the wild. This must include stopping the illegal killing and trade of tigers and their parts, conservation of tiger prey, and effective management of conflict between tigers and humans through improved livestock management, the inclusion of local people into the monitoring and management of tiger habitat, and other approaches.

Local, regional, national, and international support is needed to address other direct and indirect threats, including: economic drivers of habitat loss and illegal activity, and production and movement of pollution and other environmental stressors. A successful management towards recovery of tier populations requires mitigation of disease threats, participation and cooperation of diverse stakeholders, strengthening of conservation laws, institutions, and financial resources, reduction of graft, and changes in knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour of people and institutions that ultimately impact tigers and their habitat. A wide diversity of conservation and restoration activities are ongoing throughout the tigers range to address these challenges.

The fact that tigers no longer are present in much of their historical range presents opportunities for range expansion and targeted tiger reintroductions and translocations in the future. There now are plans to reintroduce tigers into former range countries including Kazakhstan and Cambodia.