Cheetah

Acinonyx jubatus

IUCN Red List: Vulnerable

| Weight: | 35-65 kg |

| Body length: | 113-140 cm |

| Tail length: | 60-84 cm |

| Longevity: | up to 14 years, 20 years in captivity |

| Litter size: | 4-6 cubs |

Description

- King cheetah

The cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) is, based on molecular evidence, most closely related to the puma (Puma concolor) and the jaguarundi (Herpailurus yagouaroundi). Genetically four subspecies of cheetah can be recognised:

- A. j. hecki in North and West Africa

- A. j. jubatus in Southern and eastern Africa

- A. j. soemmerringi in Northeast Africa

- A. j. venaticus previously in North Africa to central India, presently only remaining in Iran

However, as the divergence times between these lineages are very recent, further research is needed.

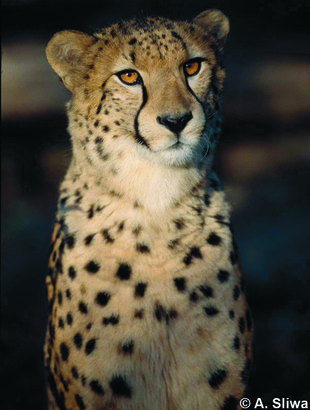

The cheetah has a tawny-coloured coat covered almost entirely with solid black spots, unlike the spots of a leopard (Panthera pardus) that are rosette shaped. Each cheetah has a unique spot pattern, often used for identification purposes. Cheetahs are easily recognisable by their heavy black lines extending from the inner corner of each eye to the outer corner of the mouth, often referred to as ‘tear lines’.

The coat colour and spot pattern of cheetahs may vary slightly - in arid, desert regions cheetahs are generally smaller and paler in colour whereas the King cheetah has much larger spots, often merging into stripes. This rare variation in the coat pattern results from a single-locus recessive genetic mutation. As it is a genetic mutation, the King cheetah is not considered as a sub-species. Individuals with this specific coat pattern are found in a small area of southern Africa. Even rarer is the spotless cheetah, a completely tawny-coloured cheetah with no black markings, last sighted in 2011 at the Athia Kapiti Conservancy in Kenya.

The cheetah is well known for being the fastest land mammal and is built for speed with an elongated body and long legs. Cheetahs have numerous morphological adaptations for speed, including:

- Long limbs, large thigh muscles and a very flexible spine - enables cheetahs to take strides up to 7 m and cover about 29 m/s.

- Semi-retractable claws - the cheetah cannot completely retract its claws thereby giving extra grip when running and turning at high speeds.

- A long tail - the tail is about half the head body length and helps the cheetah to maintain balance during their high speed hunts

- Enlarged lungs, heart and nasal passages and smaller canines relative to other felids - a reduction in the size of roots of the upper canines allows a larger nasal aperture for increased air intake which is critical for allowing the cheetah to recover from its sprint while it suffocates its prey by throttling it.

The English name ‘cheetah’ comes from the Hindi word ‘chita’, meaning ‘spotted one’. The scientific name for cheetah is Acinonyx jubatus, where Acinonyx means ‘non-moving claws’ and jubatus means ‘maned’ or ‘crested’, referring to the mantle that cubs have on their neck and back.

Language/Country | Name |

|---|---|

Arabic | fahad sayad |

Botswana (Ju/hoan Bushman; Seswana) | la'o; lengau, letlots |

Bournouan | botolo bogolo |

Burkina Faso | marukopta |

Cameroon (Fufuldé) | siho |

Democratic Republic of Congo (Kasanga) | kisakasaka |

Ethiopia (Amharic) | abo shemane |

French | guépard |

German | Gepard |

Namibia (Heikum Bushman; Ju/hoan Bushman) | /uayb; la'o |

Kiswahili | duma, msongo |

Russian | Asiaskii gepard |

Somalia | haramacad, dharab, horkob |

South Africa (Afrikaans; Zulu) | jagluiperd; ngulule |

Spanish | guepardo, chita |

Zimbabwe (Shona) | dindingwe, ihlosi |

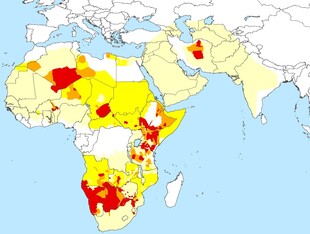

Status and Distribution

The cheetah is globally listed as Vulnerable by the IUCN Red List. The subspecies A. j. venaticus remaining only in Iran and the subspecies A. j. hecki in northwest Africa are classified as Critically Endangered. The cheetah is listed as possibly extinct in Eritrea and as regionally extinct in Afghanistan, Burundi, Cameroon, The Democratic Republic of the Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, India, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Malawi, Mauritania, Morocco, Nigeria, Pakistan, Rwanda, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Syrian Arab Republic, Tajikistan, Tunisia, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Western Sahara. In Swaziland the cheetah was reintroduced.

Cheetahs are well-adapted to dry conditions and were formerly found in savannas and arid environments right across Africa, including North Africa, all the way to the Middle East and down to south-east India. However, the cheetah only remains in 11%, 22%, and 9% of its historic range in eastern Africa, southern Africa and northwestern Africa, respectively. Today, the cheetah is primarily found throughout the drier parts of sub-Saharan Africa and is still quite widely distributed in southern and eastern Africa, with two remaining strongholds in Namibia/Botswana and in Kenya/Tanzania. However, their range is increasingly fragmented and highly restricted. The species mainly declined in western, central and northern Africa. Much of the cheetah’s range lies in the Sahara,where it occurs at very low densities of 0.023 individuals per 100 km2. In Asia, the cheetah has disappeared from almost its entire historic range. Iran is the only country where a small population of Critically Endangered Asiatic cheetah persists. The Asiatic cheetah is believed to be divided into three subpopulations occurring in northeastern Iran, central Iran and in Kavir national park. The main causes for its disappearance were probably the depletion of its wild prey base, habitat alterations, direct killing and the illegal capture of live cheetahs. Seventy-seven percent of known cheetah range lies outside of protected areas.

A large part of the current cheetah population (67%) lives outside protected areas in regions where lions and spotted hyenas have been extirpated. Density and abundance vary widely according to environmental conditions. In the Serengeti plains the density was estimated to range from 0.8 to 1.0 / 100 km². Density in well managed protected areas was estimated at 1 / 100 km² and the density in largely unprotected areas was estimated at 0.25 / 100 km² individuals. The density in Saharan habitat was estimated at 1 / 4,000 km², and density of two subpopulations in West and Central Africa was estimated at 0.1 mature adults / 100 km². All known cheetah populations are relatively small, two thirds are comprised of less than 100 mature adults, and for many countries their numbers are not known. The number of mature individuals is tentatively estimated at 6,517 animals and the number of subpopulations at 33. Of these 33 populations, only two have an estimated size of over 1,000 mature individuals, two thirds comprise fewer than 100 individuals and six fewer than ten individuals. Of 18 populations where trends could be assessed, 14 were declining, three were stable and one was potentially increasing.

Region/subpopulation | Estimated population |

|---|---|

Southern Africa | 3,526 adults |

Transboundary landscape covering southern Botswana, Namibia, southern Angola, northern South Africa, and south-western Mozambique | 3,396 |

Moxico region, central Angola | 23 |

Banhine National Park, Mozambique | 9 |

Kafue National Park, Zambia | 60 |

Liawu Plains, Zambia | 18 |

Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe | 46 |

Gonarezhou National Park, Zimbabwe | 42 |

Southern Zimbabwe | 37 |

Zambezi Valley, Zimbabwe | 11 |

Rhino Conservancy, Zimbabwe | 4 |

Matasudona, Zimbabwe | 3 |

Eastern Africa | 2,102 adults |

Ogaden Landscape, Ethiopia | 29 |

Blen Afar Landscape, Ethiopia | 18 |

Afar Landscape, Ethiopia | 10 |

Yangudi Rassa Landscape, Ethiopia | 7 |

Serengeti/Mara/Tsavo/Laikipia Landscape, Kenya/northern Tanzania | 1,250 |

South Turkana, Kenya | 33 |

Transboundary population southern Ethiopia, eastern South Sudan, and northern Kenya | 175 |

Southern National Park, South Sudan | 135 |

Badingilo National Park, South Sudan | 78 |

Radom National Park, South Sudan | 62 |

Katavi-Ugalla Landscape, Tanzania | 55 |

Maasai steppe, Tanzania | 47 |

Ruaha, central Tanzania | 184 |

Kidepo National Park, Uganda | 17 |

Western, Central and Northern Africa | 419 adults |

Adrar des Ifhogas/Ahaggar/Tassili N'aijer Landscape, Algeria and Mali | 175 |

WAP complex, Beinin, Niger and Burkina Faso | 23 |

Bahr/Salama Landscape, Chad and CAR | 218 |

Air et Ténéré (connected to Termit Massif, Niger) | 2 (connected to another 1–2) |

Asia | < 50 adults |

Iran (subspecies A. j. venaticus) | 14 |

Habitat

The cheetah inhabits open grassland and savannah habitat. It is also found in dry forest, semi-desert, open woodlands and shrubland and is absent from the tropical rainforest. In the central Sahara, the cheetah can be found in high mountain habitat which has slightly more rainfall than the surrounding desert. The cheetah in Iran inhabits plains and saltpans, eroded foothills and desert ranges with precipitation lower than 100 mm per year. It occurs up to an elevation of 2,000 – 3,000 m and on Mt. Kenya cheetahs were recorded up to 4,000 m.

- Cheetah habitat in Kwara, Nigeria.

- Two cheetahs resting in the shadow in the Serengeti.

Ecology and Behaviour

The cheetah is mainly active during the day. Whilst this diurnal activity is believed to reduce competition with nocturnal predators, such as lions and spotted hyenas, recent studies have shown that cheetahs are surprisingly active at night and that this activity is positively correlated with the amount of moonlight available.

The social organisation of cheetahs is unique among felids. After cheetahs leave their mother, male and female litter mates will usually stay together for about six months before splitting and going their separate ways. Once split, females will remain solitary, or are accompanied by dependent young, while males will either be solitary or form a coalition, or group, with other males. Coalitions usually consist of 2-3 males, usually related individuals, but can also be unrelated individuals. Male coalitions are more likely to gain and maintain territories than solitary males. Female cheetahs do not show mate fidelity and tend to mate with multiple males.

Whilst females are non-territorial, male cheetahs can establish small territories that typically contain resources such as prey to attract females. However, not all males are able to acquire a territory; coalitions are more able to hold territories than single males as they are more powerful and therefore have a competitive advantage. Females and non-territorial males have large and overlapping home ranges. The sizes of home-ranges vary immensely between the studies that have been carried out in different areas. In Kruger National Park and Matusodona National Park home-ranges for both semi-nomadic females and males are >200 km², in Serengeti National Park they are around 800 km² and in Namibia they are on average 1,595 km². In areas with migratory prey, cheetahs without territories namely tend to follow their prey around. Territories established by territorial males are significantly smaller than home-ranges and will rarely overlap as these are areas that contain defensible resources such as prey, water and mates. It is hypothesised that cheetahs have their unique social structure and wide-ranging patterns to avoid competition with larger and stronger predators. Similarly, their low density may be limited by interspecific competition or prey availability.

Males, whether territorial or not, scent-mark to advertise their presence by spray-marking, scratching, and defecating on prominent features in the landscape; such features may include termite mounds, shrubs, fallen branches and trees. Marking trees, also known as ‘play trees’ are the preferred feature and are typically large, conspicuous trees to which the cheetah returns repeatedly.

The cheetah is well adapted to live in arid environments and as such is not an obligate drinker, satisfying its moisture requirements by drinking the blood or urine of their prey or by occasionally eating tsama melons.

The reproductive season is year-round although birth peaks have been reported during the rainy season in the Serengeti. Both sexes will mate with several partners and a genetic study revealed that cubs of the same litter can have different fathers. Age at first reproduction for females is 24-36 months and 30-36 months for males. Age at last reproduction for females is 10 years and for males up to 14 years. The gestation period lasts for 90-98 days and the inter-birth interval ranges between 15-19 months. Once a female has lost her litter, she will quite readily go into oestrus and conceive. Cheetah cub mortality is high - over two thirds of cubs die during their first two months mostly due to predation by other carnivores, especially lions, spotted hyaenas and leopards. Smaller predators such as jackals, secretary birds and honey badgers, however, can also contribute to cub mortality. In the Serengeti, Tanzania it was found that only 5% of cubs reached independence while in the Kgalakgadi Transfrontier Park, South Africa/Botswana about 35% of cubs survived to independence. Age at independence is around 13-20 months when sub-adults leave their mothers and within 6 months of leaving their mums, females leave their sibling groups while surviving males can stay together for life.

The cheetah is a high-speed cursorial hunter, reaching speeds of up to 103 km/hr during a chase. As cheetah’s prey might be weaving and they have to circumvent obstacles, actual chasing speeds, however, might be lower than this. The cheetah will generally first stalk its prey before chasing the prey at full speed over relatively short distances, seldom more than 300m. When prey is abundant, cheetahs tend to hunt every 2-5 days except when a female has cubs, then hunting becomes a daily activity. Cheetahs rarely scavenge and can lose to up to 10% of their kills to other larger carnivores. To avoid competition with other predators they generally hunt during the day and do not stay with their kill long.

- Cheetahs in Kwara, Nigeria.

- Male cheetah marking.

- Cheetah cub.

- Cheetah in Kwara, Nigeria.

Prey

The cheetah tends to prefer the most abundant prey species with a body mass range from 10-56 kg This includes impalas (Aepyceros melampus), gazelle (Gazella spp.), kob (Kobus kob), springbok, warthog and other antelopes but will also prey upon smaller animals such as hares or birds. Coalitions of males can take larger prey such as wildebeests, kudu, or eland. When cheetahs hunt herd animals, they tend to select the less vigilant individuals and depending on the season they capture mostly immature animals. In east Africa the cheetah’s main prey is the Thomson’s gazelle on the plains and the impala in the woodlands. In northern Kenya its major prey are lesser kudu, gerenuk and dik dik, and in southern Africa it mainly preys on springbok, greater kudu calves, warthog, impala and puku. In Iran, cheetahs main prey include wild sheep, Persian ibex and cape hares. There is very little evidence of livestock consumption by the Asiatic cheetah.

Cheetahs rarely defend their kills and as such kills can be stolen by the comparatively larger carnivores such as lions and spotted hyenas. For example, in the Serengeti, Tanzania, cheetahs lose up to 12.9% of their kills, of which 78% were taken by spotted hyenas and 15% by lions. The cheetah rarely scavenges or returns to a previously abandoned kill.

- Cheetah with its kill.

- Cheetah hunting.

- Cheetahs watching a prey in Kwara, Nigeria.

Main Threats

The main threats to the cheetah are habitat loss and fragmentation, land use change, retaliatory killing and prey base depletion due to overhunting, bushmeat harvesting and illegal trade, which often leads to higher predation on livestock and therefore to more conflict with humans.

Habitat loss and fragmentation are the main threats and are largely a result of changes in land-use management, increase in resource extraction and extensive infrastructure development, and climate change. Fragmentation and encroachment of the cheetahs’ habitat can result in discontinuous subpopulations, a decrease in prey availability and an increase in predator densities, causing a higher level of interguild competition and increased contact with humans and their livestock.

A major threat to cheetahs is also a reduction in their natural prey base, predominantly caused by human activities such as hunting and livestock grazing. Another threat is the illegal trade of skins and live cheetahs. The majority of this trade includes the live trade of cheetahs. It is quite common to shoot the mother and take the cheetah cubs in order to sell them on the black market and there is an increased trade in cubs from northeast Africa into the Middle East. Most live cheetahs seem to be traded from the Horn of Africa and surrounding regions into the Gulf States. Many captured cubs already die during the transport. In Somaliland and Ethiopia, the mortality rate is as high as 70% among confiscated cubs, with actual number likely being even higher as many dying cubs might never be detected. When kept in captive conditions, cub survival is also likely to be low as they are kept in inappropriate conditions. Cheetah populations in the Horn of Africa are likely to be most affected by the illegal trade in live animals. Skins of cheetahs are traded within Africa and to Asia.

Despite intensified conservation and education efforts and the fact that research shows that cheetahs are only responsible for few livestock losses to predators, human-wildlife conflicts are still an issue. Farmers often still consider cheetahs as a problem and a threat to their livelihood. It is thought that excessive tourism and poor wildlife observation practices can affect cheetah hunting success, reproductive success and cub mortality. Cheetahs get occasionally also captured in snares set for the bushmeat trade.

The cheetah is wide ranging and occurs at very low densities. Thus, it needs large areas to survive. Most protected areas are not large enough to sustain viable populations and the majority of cheetahs lives outside of protected areas on farmland exposing them to higher risks of conflicts especially with livestock and game farmers. Cheetahs prefer wild prey but, in some circumstances, they also take livestock. This can lead to retaliation killing of the cheetah due to depredation or to prevent livestock losses. Game farmers see them as competitors for valuable game offtake. The cheetah is considered to be vulnerable to interspecific competition from other large carnivores, especially lions, which can limit cheetah abundance by killing their cubs or even adults. High speed roads also pose an increasing threat to the wide-ranging cheetahs. Additionally, unregulated tourism too can threaten cheetahs as this can interfere with their hunting behaviours and can result in cub mortality due to separation of them from their mother.

Genetic analysis has shown that both captive and free ranging cheetahs exhibit a very high level of homogeneity in coding DNA and have high levels of abnormal sperm. The cheetah appears to have suffered a series of severe population bottlenecks in its history which may have led to inbreeding of few surviving individuals. Based on mitochondrial DNA the first such bottleneck may have taken place during the late Pleistocene extinctions around 10,000 years ago. Although these ancient population bottlenecks are not clear both their causes and consequences could be of significance to cheetah conservation today. This lack of genetic diversity makes the cheetah exceptionally vulnerable and potentially susceptible to diseases such as mange (within the Serengeti-Mara ecosystem) and anthrax (in Etosha). Their low density, however, makes infectious diseases less likely to pose a major threat to free-ranging cheetahs.

In eastern, southern and western Africa, habitat loss and fragmentation have been identified as a primary threat. Additionally, (perceived) livestock depredation poses a problem across most of the cheetah’s range. In the deserts of Northern Africa and Iran a depleted wild prey base is of great concern as well. Due to the wide-ranging spatial patterns of cheetahs, large-scale land management planning is required to connect viable populations.

The aforementioned threats are all proximate causes of cheetah decline driven by ultimate drivers such as political constrains, a lack of capacity and resources to support conservation, a lack of environmental awareness, rising human populations and a lack of incentive for local communities. In order to address the immediate threats, these drivers must be addressed.

Conservation Efforts and Protection Status

The cheetah is included in Appendix I of CITES and it is fully protected throughout most of its range. Moreover, the cheetah is included in Appendix I of the CMS. Hunting is prohibited in Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zambia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Iran and Afghanistan. Trophy hunting is permitted in Zimbabwe and in a number of countries it is legal to kill cheetahs in defence of life and livestock. No information is available for Chad and Sudan.

One important conservation measure for the cheetah is the promotion of better livestock management to reduce conflicts with humans. Another measure is the assurance of enough prey availability to the cheetah in an attempt to reduce livestock depredation. Further measures include the improvement of monitoring, surveys and information exchange as well as capacity building, the promotion of human-cheetah coexistence, enforcement of policy and legislation along with the insurance that national land use planning allows viable cheetah populations. In Iran, the safeguarding of roads too is an important conservation measure.

To improve cheetah conservation several networks have been established such as the Global Cheetah Forum and the North African Regional Cheetah Action Group. Most of the range states are involved in the African Range-Wide Cheetah Conservation Initiative formerly known as the Range Wide Conservation Program for Cheetah and African Wild Dogs. This program supports the development of Regional Strategies and National Action Plans, according to IUCN guidelines. A global conservation strategy for the cheetah has been developed and several range states have created national action plans or conservation strategies. Three regional conservation strategies have been developed for Africa: one for Southern, one for Eastern and one for Western, Central and Northern Africa. National Action Plans are in place for Algeria, Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Chad, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Tanzania, South Africa, South Sudan, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Cheetahs are also included into the Large Carnivore National Conservation Action Plan of Uganda. These plans cover 96% of the known extant cheetah range. All these plans address both proximate threats and ultimate drivers of these threats. They all broadly include the improvement of national capacity for cheetah conservation and management, awareness raising of and political commitment to cheetah conservation, promotion of human cheetah coexistence, improvement of land use planning and reduction of habitat fragmentation, improvement of policy and legislation and the information needs for cheetah conservation.

The cheetah is also part of the CITES-CMS Africa Carnivore Initiative, which includes decisions to improve the conservation status of the cheetah.

Conservation work is challenged at many levels: unstable political situations, non-existent enforcement where conservation regulations are in place, lack of incentives for local people to be engaged in conservation efforts, the need to raise awareness of conservation and environmental issues, little or no capacity and financial means to support a conservation approach and generally pressures from a rising human population.